PhD Defense Q. Ruan MSc

Management Control Systems and Ethical Decision Making

- Location: Cobbenhagen building, Aula

- Supervisor: Prof. E. Cardinaels

- Co-supervisor: Dr. H. Yin, Dr. J. Willie CHoi

We still offer a live stream for our ceremonies.

Research summary

Ethics are pervasive and thus complex: it has different facets in different contexts. Very often, people discuss ethics case by case and find it very difficult to have a holistic thinking path about how to improve ethics. My research aims to develop a systematic framework to guide thinking on how to improve workplace ethics through management control systems.

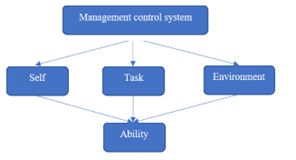

To answer the question, I first decompose the concept of ethics into the individual component, the social component and the intersection of the two. Is ethics purely an individual concept? Is ethics purely a social concept? The answers are no to both. Ethics can be viewed a combination of both. On the one hand, we care about how good/bad we feel about our behaviors. On the other hand, what is good/bad comes from our understanding of the social norm, and we also care about how others feel about us. Thus, we can divide ethics into three components, with the individual extreme as self, the social extreme as environment. What lies in between, in a typical managerial context, is the task (shown in Figure 1).

The three papers in my dissertation examine each dimension of the framework (self; task and environment). On the dimension of self, an important question is “what is my self-concept?” We all like to think we are good people, but how good we are concretely is quite ambiguous. If information is provided on our position on the social dimension, can we learn something about self-concept and make better ethical decisions afterwards? Paper 1 looks at an employee giving context and argues that relative performance information on the social dimension (i.e., contribution) helps employees update own self-concept and behave more ethical afterwards. The effect is driven by employees with high or medium level of donation engagement, suggesting that companies can incubate an ethical norm within an organization through the employee giving programs, by jointly disclosing relative contribution information and engaging employees into donation. The research also highlights the importance of informativeness of the information, that ethical learning only materializes in money donation but not in time donation, highlighting the need to consider the donation type when revising the information policy.

Turning to the dimension of task, a key question when people are doing the task is “why am I doing this?”. If we can shape task motivation, we might be able to influence ethics. Paper 2 looks at an employee learning setting. Such setting is crowded with business scandals of employee cheating. For example, one of the big four accounting firms KPMG received 50 million dollars fine from SEC for auditor’s cheatings on internal training. Another big four accounting firms EY also received 100 million dollars fine for employees’ cheating behavior. This paper aims to understand what the motivational mechanism for unethical learning practices is and finds out that a popular practice, though advocated by practitioners—outcome transparency (e.g., using leaderboard on learning performance) unintendedly harms the learning orientation—people start to feel the reason for learning is mere completion rather than acquiring the knowledge. The paper also identifies a solution—introducing a personalized learning path (i.e., giving employees autonomy over what to learn and how to learn). This helps to activate employees’ curiosity and reduce adoption of unethical learning practices.

The last part of the framework is the dimension of the environment. When siting in an environment, a key question is “what is the vibe of the environment?”. If we can shape a vibe that facilitates the ethical thinking mode, then we may elicit more ethical decisions. Paper 3 looks at the internal reporting context and examines whether the reporting device we use can institutionalize different thinking mode. Traditionally employees use computer for internal reporting, with the prevalence of hybrid working mode, more employees use personal mobile phones to report. Compared to the traditional reporting device such as computer, the personal phone may activate more person feelings when employees are making decisions. The research finds out that such personal feelings push people to consider own behaviors (i.e., misreporting) in a more prosocial way and report more honestly. The research also finds that a boundary condition for this effect to materialize—employees’ mindfulness, suggesting that investment into attention-management resources is key to reap the potential ethical benefits of mobile reporting.

All three papers illustrate how each dimension in the framework can be used to explore novel opportunities to improve employees’ ethical decision making. Even though each paper looks at one specific setting (employee giving; employee learning; internal reporting), the framework can also be useful to guide thinking in a couple of emerging managerial practices such as ESG, supply chain and artificial intelligence. I am excited about using my framework to explore ethical issues in these emerging and important settings.

Figure 1.