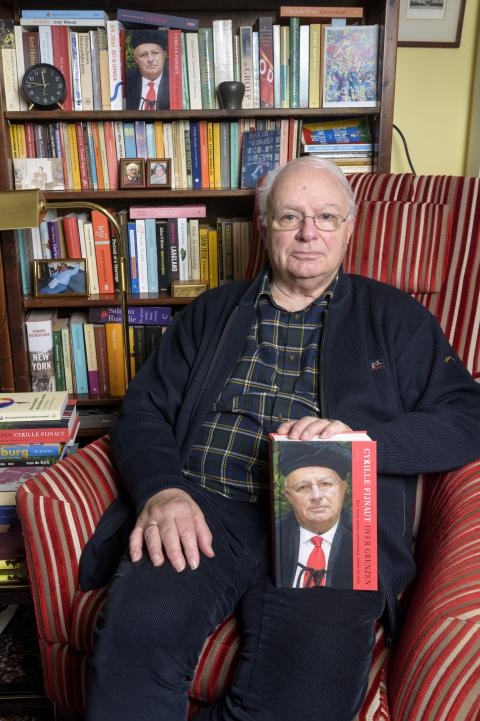

Memoirs Cyrille Fijnaut, tireless fighter against organized crime and for disseminating knowledge

When he retired from the university, Emeritus Professor of Criminology and Criminal Law Cyrille Fijnaut already announced that he still had lots of work to do, that is, lots of books to sort and archives to clear away, approximately seventy of the latter, spread over four rooms in his home. The idea was that this clean-up would generate publications. The first promise has been kept: his memoirs have recently been published by Prometheus. Entitled Over Grenzen (“Across Borders”), the book is already in its second printing. Based on many anecdotes, we become better acquainted with former police officer Fijnaut, as a doer, an ‘activist’ by his own account, within the boundaries of the law, of course. And a sought-after expert who advised governments, our own, the Belgian government and also that of South Africa, at Nelson Mandela’s request.

It all started small and local, however. As the son of a much-respected police officer in Heerlen, he observed his father: his dad often took him in tow and had many and extensive contacts in the community. As a result, he was appreciated and also well-informed, a lesson that little Cyrille took to heart, which proved a great benefit later. When he had finished his pre-university education, it was clear that he was attracted to policing, too, and he continued his studies at the Dutch Police Academy and then took Criminology and Philosophy at KU Leuven.

Fijnaut got a job in Tilburg as an inspector of police and was approached in 1969 by chief of police Van Rijen because of some trouble at the university of Tilburg, where protests were being held, calling for more student participation in decision-making. When the students proceeded to occupy the campus buildings and renamed the university “Karl Marx University”, the authorities were in a quandary whether or not the city or the government should step in. ‘The chief of police asked me to go to the campus and observe things. After all, the going-on constituted a disturbance of public order. The occupation of the university was an extraordinary event, the first in the country and a shocking thing to behold for upper middle-class Brabant.’

‘Yet, it was in fact quite a leisurely affair, even though some students acted like gladiators. Most protesters were well-behaved boys and girls, quite harmless, but there were a few rabid radicals among them. However, the general public had the impression that all hell had broken loose in Tilburg. So I was also on the campus and in the Auditorium. It wasn’t very exciting, until the moment when they went to the board room. I slipped into the room after them; nobody asked what I was doing there. They demanded that the governor, Loevendie, introduce reforms. Strong language was used, there was some arguing and shouting, true, but the governor kept his cool and nobody got hurt.

It doesn’t pay to seek confrontation; it can only lead to people digging their heels in

Emeritus Professor of Criminology and Criminal Law Cyrille Fijnaut

I biked back to police headquarters and advised the chief of police not to intervene on campus since it would only have fueled the conflict. I had been in Paris in 1964 and had seen up close how police cracked down on students. You don’t want that.’ In his memoirs, Fijnaut describes how he sympathized with the occupiers: ‘Deep down, I’m an activist.’ He thinks his advice at the time is still relevant. ‘It doesn’t pay to seek confrontation; it can only lead to people digging their heels in. You have to have preliminary discussions with the leaders first and then you set the framework. That is also reflected in the current police response to the farmers’ protests: you need to make contact first, and talk. That prevents escalation.’

Nelson Mandela and ‘security triangles’

He also suggested this modus operandi in 1993, when he was approached by Richard Goldstone. This South African judge had been asked by Nelson Mandela, who had just become president of South Africa, to set up a commission to prevent bloodshed between police and protesters. ‘Police officers there were used to shooting at protesters with birdshot, these large pellets. The police only had one answer. Mandela wanted to put a stop to this, or he would never get down to the business of governing, he said. Goldstone convened a group of five international experts at the Business School of Capetown University and locked them up for ten days to come up with a plan. We proposed to introduce three-way consultations, consisting of the mayor, the police, and relevant organizations. These consultations served to jointly discuss, prior to any protests, whether and how they were allowed to go ahead. Some special units were disbanded. And the government modernized the police force.’

He is a go-getter at heart, but not only that. He shows his ex libris adorning the inside of the cover of his new book: a small owl, its eyebrows forming an open (statute) book, standing on a sword (representing the state’s monopoly on the use of force). All his work is grounded in practical experience and academic insight, and stems from hard work and diligent study. As a result, Fijnaut became a much sought-after expert, particularly in the field of organized crime. He was praised for his integrity and unassuming frankness. One of his achievements was supporting the 1995 Van Traa Parliamentary Committee of Inquiry, which investigated the methods of investigation used by the police and judicial authorities in fighting organized crime in the Netherlands, and drafted new legislation.

In 2004, Dutch Minister of Justice Donner asked him to give advice on the restructuring of the special units so they would be able to cope with terrorism in the wake of 9/11, so with suicide attacks aimed to make as many victims as possible in public places.

And then there was Tilburg mayor Johan Stekelenburg, who approached him at the end of 2002 asking him and a commission of experts by experience to write a report on ways to improve the social safety in the city. It was around the time that Dutch politician Pim Fortuyn was assassinated during the 2002 Dutch national election campaign. To this end, the Fijnaut Commission developed the construction of the Safety House, in which different organizations coordinate efforts to prevent young people from becoming career criminals. With the help of Justice Minister Ernst Hirsch Ballin, this idea was subsequently adopted in all the larger cities and regions.

Stepping up the game – to Olympic levels

In the last couple of years, he has been much in the news, criticizing the national approach to organized crime. ‘The biggest problem is that even though all kinds of facilities are in place, no coherent strategy has yet been developed, the implementation of which is systematically directed and coordinated from one central point. In addition, there are a couple of other threats. One of them is the fact that much-needed united action in criminal investigation at a national level is being compromised by a battle of conflicting interests between the “old” national services, such as the Dutch Tax and Customs Administration/Fiscal Information and Investigation Service, and the establishment of another new one, the NSOC (National Cooperation against Organized Crime; the successor of the Multidisciplinary Intervention Team, MIT). The resulting underfunding of very important investigations at district and regional levels is another. Be that as it may, fortunately there has been some catching up in the past few years, policy-wise as well as financially, also in the online context, e.g., with the expansion of the High-Tech Crime Unit. However, organized crime has only expanded too, in the meantime, even to cities like Groningen and its countryside.’

The government will need to put much more effort into cutting criminal careers short through heavily investing in the Safety Houses

‘What needs to be done is concentrating policy and resources. First of all, the heads in organized crime must be brought to account via criminal and fiscal procedures. This is very important, if only to prevent them from becoming role models to young people, but this alone is not enough. The government will need to put much more effort into cutting criminal careers short through heavily investing in the Safety Houses. And finally, the criminal infrastructures need to be taken down as quickly as possible, especially those of the drug industry.’

The problems in the field of organized crime have become much more complicated than they used to be. ‘I am really worried about developments in the Netherlands, with the murder of people like state witness lawyer Derk Wiersum and investigative journalist and crime reporter Peter R. de Vries. How can it be that, in this country, people face threats by the underworld to such an extent that they cannot live normal lives? That successive governments, authorities, and services should have let things come this far?’

Addressing those problems thus requires a clear strategy and that also means training, especially for management in police, administration, and justice and those working for Tax and Customs. ‘Heavily investing in education is sorely needed there. They need to step up their game – to Olympic levels. That a senior member of the National Police has publicly stated that the force has no resources for protecting crown witnesses for the time being is outrageous. Major criminals now know that, on one very important point, they have much more scope to continue their objectionable practices. We are talking one of the most serious issues in our country here! It testifies to the terrible incompetence I have been fighting against for years. I presume that the leadership of the prosecution service and the Minister of Justice and Security gave the person involved a good talking to. Otherwise we are even further up the creek.

And at 77, he has not yet completed his mission. Two more books are scheduled. And he further shares his expertise by donating his scientific library, consisting of ten thousand volumes, including 600 on the mafia, and his archives to the Dutch Police Academy and the National Archives of the Netherlands.