Togetherness in the Household

Most people consider at some point in their life whether to enter a relationship with another person, that is, whether to form a couple with a partner. When considering the gains from marriage/partnership, one of the first ideas that comes to mind is togetherness, namely the time spent together with the partner.

Surprisingly, little is known about how couples value togetherness, what benefits and costs it accrues, or how it interacts with other uses of time. We address these issues in our new paper Togetherness in the Household, which will appear in the American Economic Journal - Microeconomics. [i]

-

dr. Alexandros Theloudis

Assistant Professor

TiSEM: Tilburg School of Economics and Management

View full profile

TiSEM: Department of Econometrics and Operations ResearchA.Theloudis@tilburguniversity.edu Room K 508

- Sam Cosaert

- Bertrand Verheyden

The data

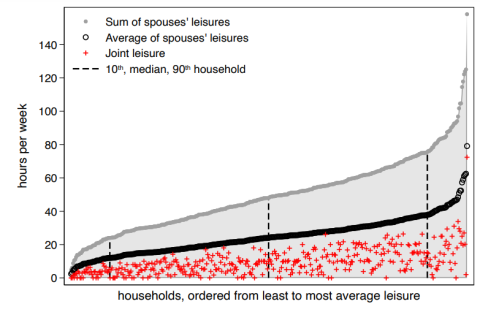

Recent survey data from the Netherlands [ii] suggest that partnered individuals spend substantial amounts of time together. Figure 1 shows that over 90% of Dutch households report some joint leisure, namely leisure in the company of each other. Often, joint leisure is almost one half of each person’s total leisure.

Figure 1 Weekly leisure: Aggregate and joint

Note: We sort households with respect to aggregate leisure, i.e. the sum of spouses’ total leisure times. Source: Longitudinal Internet Studies for the Social Sciences 2009-2012 (LISS).

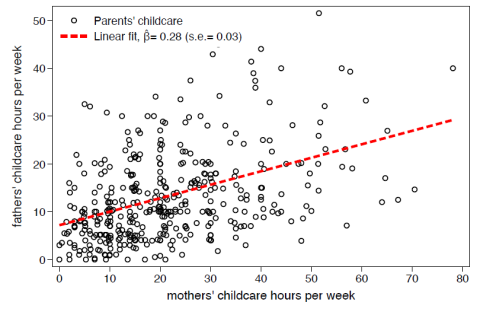

Togetherness is not limited to joint leisure; childcare may also be joint between partners. We do not observe joint childcare (it is rarely observed in survey data) but we observe the overall time each parent spends on childcare, comprising care done jointly with his/her partner and childcare done alone. Figure 2 shows that in the vast majority of households both mothers and fathers do childcare, and the amounts of childcare are positively correlated between them. Joint childcare is a possible interpretation for this correlation.

Figure 2 Weekly childcare: Mothers and fathers

Note: Despite common perception, only 2% of fathers do not do any childcare at all.

Source: Longitudinal Internet Studies for the Social Sciences 2009-2012 (LISS).

So the data suggest that togetherness, be it in the form of leisure or in the form of childcare, is a substantial part of family time use. But is togetherness for free?

The benefits and costs of togetherness

Joint leisure is desirable on the grounds of companionship. Joint childcare is beneficial on child developmental grounds; it enhances communication and closeness in the family and improves children’s verbal and other cognitive skills.[iii] Both joint leisure and joint childcare have significant costs.

First, togetherness requires spouses to synchronise their schedules to be physically together at the same time. This implies that those who prefer joint time may have to renounce a job that requires flexibility. Yet, being flexible at work is often associated with a wage premium, for instance in high-responsibility occupations where work schedules are irregular or unpredictable. Consider a household in which the husband has a regular work schedule but the wife, perhaps due to the nature of her job, has an irregular or unpredictable work schedule (e.g. a doctor being on call). This household likely enjoys less togetherness than another one in which both spouses have regular work schedules. Togetherness requires synchronization of schedules which may be impossible if the timing of work is irregular, thus impossible without restricting one’s flexibility at work and possibly reducing her earnings.

Second, while joint childcare may improve the quality and impact of care, it hampers division of childcare duties between partners and hurts specialization in the household. Young children typically need attention for a given amount of time, say 8 hours per day, which usually requires only one adult. Suppose that each parent has 4 hours available per day for childcare. If parents supply childcare privately, they supply 8 hours in total. If they supply it jointly, they only offer 4 hours while for the remaining time care must be provided by another, perhaps costly, caregiver.

A model of family time use

We develop a model of family time use featuring the above-mentioned benefits and costs of togetherness. To capture the possibility that togetherness incurs a loss of flexibility at work, we introduce different market work schedules over the day, and we give each spouse a choice over them. To capture the possibility that joint childcare incurs the loss of benefits of specialization in the household, we introduce mandatory childcare over a certain amount of time. This can be carried out either by each parent alone, or by both of them together, or by an external caregiver.

The model allows us to understand how time use (including joint and private uses) is affected by economic circumstances, such as wages in the labor market, the timing of market work, or the costs of day nurseries. It also allows us to monetize the additional value (if any) that joint time has over private time, and estimate the amount of joint childcare in the household – a component not typically observed in survey data.

Based on survey data from the Netherlands, (ii) we find that households pay on average €1.2 per hour (10% of the hourly wage) to replace private leisure with joint, and €2.1 (17% of the wage) to replace private childcare with joint. These numbers show the extent to which couples value togetherness in leisure and childcare. In addition, parents spend up to 12 hours per week on joint childcare, representing 92% of total childcare by the father.

Togetherness and the gender gap

Our model suggests that the spouse who works fewer hours in the labour market is also the person who forgoes work flexibility in order to increase togetherness. In the Netherlands, women work fewer hours than men due to lower pay or other reasons. Our model suggests that women will then restrict flexibility on the job to synchronise work with their husband’s and increase togetherness. Women, not men, forgo flexibility because it is less costly for them to align their fewer work hours with their husbands’. If flexibility pays a premium, women then forgo such premium. This is consistent with Claudia Goldin’s and other scholars’ argument [iv] that women’s inflexible timing of work reinforces any preexisting gender wage gap. In spite of this, we also argue that togetherness mitigates intra-household inequality in the sharing of resources between spouses, at least vis-à-vis a setting with private times only.

Contact details

- Alexandros Theloudis

Department of Econometrics & OR

Tilburg University

a.theloudis@gmail.com

@AlexTheloudis

Notes:

[i] Cosaert, S., A. Theloudis, and B. Verheyden (2022). Togetherness in the Household. Forthcoming at American Economic Journal Microeconomics. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/mic.20200220.

[ii] LISS Longitudinal Internet Studies for the Social Sciences over 2009-2012. CentERdata, Tilburg University. https://www.lissdata.nl/Home.

[iii] Cano et al. (2019) and Le Forner (2021) study the impact of joint parental time on children’s cognitive and non-cognitive skills; in both papers joint time is paramount for children’s verbal skills and communication. See: Cano, T., F. Perales, and J. Baxter (2019), A matter of time: Father involvement and child cognitive outcomes, Journal of Marriage and Family 81 (1), 164–184; and Le Forner, H. (2021), Formation of children’s cognitive and socio-Emotional skills: Are all parental times equal?, unpublished manuscript.

[iv] See, for example, Goldin, C. (2014), A grand gender convergence: Its last chapter, American Economic Review 104, 1091–1119; and Olivetti, C. and B. Petrongolo (2016), The evolution of gender gaps in industrialized countries, Annual Review of Economics 8, 405–434.