Large wild animals are key to biodiversity recovery

We are living in an age where crises are hot on each other’s heels, but the one to potentially top them all is the biodiversity crisis. And to tackle the biggest of all crises, we must also think big, says environmental law researcher Arie Trouwborst. One of his interests is the return of megafauna – large wildlife such as wolves and European bison but perhaps also lions and elephants – to Europe.

In our collective memory, the natural habitat of big wild animals is in Africa and Southeast Asia. In Europe, we are more likely to think of bees, sparrows, and lapwings as species under threat of extinction. This is a classic case of shifting baseline syndrome: each generation only remembers the species that were prevalent in their childhood. In other words, Arie Trouwborst contends, we suffer from collective amnesia: we have completely forgotten the large animals that for millions of years played a key role in European ecosystems. Animals such as wild horses and cattle, moose, European bison, lions, and hyenas, but also rhinoceros, mammoths, and straight-tusked elephants. The rise of homo sapiens, starting about 40,000 years ago, put an end to their dominion.

Restoring megafauna

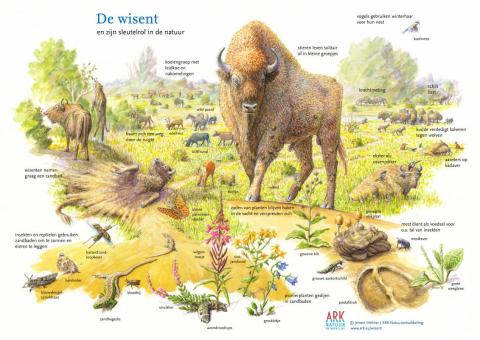

Current ecological wisdom suggests that to restore our ecosystems we ought to restore the megafauna that populated the planet before they were wiped out. Large mammals help nurture robust and rich ecosystems that are far less vulnerable to climate change: the soil recovers, biodiversity increases, water balance improves, and the effects of droughts, wildfires, and flooding diminish. In addition, such healthy and dynamic ecosystems sustain themselves; no human intervention is needed.

This begs the question whether we can coexist with large wildlife in Europe. “We can’t turn back the clock 50,000 years,” Trouwborst says, “but there is a gold standard of approximating flourishing ecosystems with a large biodiversity as closely as possible. That standard includes large numbers and a large variety of big mammals.”

The law as lever and as obstacle

As a lawyer, Trouwborst’s focus is on clarifying the role of law in all manner of ecosystem restoration scenarios. That role can be a positive one, as the return of wolves to the Netherlands shows: the legal protection of wolves at the European level proved decisive. There are also international obligations to actively reintroduce threatened species such as the European bison, as is indicated in research conducted by Trouwborst and Danish ecologist Jens-Christian Svenning. One such international source of law is the 1992 UN Convention on Biological Diversity , which stipulates that degraded ecosystems must be rehabilitated and restored “as far as possible and as appropriate”.

European policymakers have a blind spot when it comes to species that have disappeared

But who still knows that moose were once indigenous to the Netherlands or that hyenas roamed Europe? “European policymakers have a blind spot when it comes to species that have disappeared,” Trouwborst says. That is why he and Svenning listed all species of large European mammals weighing over 10kg that would have occurred in Europe today but for human interference: 74 in all. Over half of them have died out, with the heavier species having the doubtful honor of being the strongest extinction candidates. Once extinct, no species can be reintroduced, but serious thought has gone into recovery experiments using “replacement” species, such as the Asian elephant.

But law does not only benefit nature recovery; it also raises barriers. Under agricultural law, disease must be prevented through inoculation and disposing of carcasses. Some of these rules also apply to the semi-wild cattle and horses that have been successfully reintroduced to several Dutch floodplains and to the Oostvaardersplassen, a large protected natural area. Trouwborst: “The legal issue is what status these animals have. Do we have a duty of care towards them or a duty to leave them be? We need to create an effective legal status, and de-domesticated horses and cattle should ideally regain the official status of indigenous wildlife.”

Societal reluctance

It is not just agricultural law that throws a wrench in the works; there is unwillingness in society at large to make room for wild animals. That reluctance to co-exist with cumbersome animals was of course the very reason they were wiped out in the first place. A good contemporary example is the resistance to the first few wolf packs that returned to the Netherlands. “It’s always hard to change the status quo; it is up to the government to take control,” Trouwborst says. Rest assured: Dutch backyards will not be thronging with hyenas overnight, but there are sparsely populated areas in Europe where long-lost wildlife might return. Trouwborst: “Why should we welcome wolves and lynx, but keep out leopards and black bears? Strictly speaking, they are just as indigenous. In many parts of Europe, agriculture has ceased to be profitable, and it is there that nature restoration projects featuring large, charismatic animals might even give the countryside a boost.”

We have a moral duty to restore European megafauna

Europe might learn a thing or two from wildlife management in African wildlife areas. Trouwborst even goes so far as to argue that we have a moral duty to restore European megafauna. Not only because we must restore what our own species has destroyed, but also because we should not pawn off the responsibility for preserving endangered animal species (such as lions, leopards, hippopotami, rhinoceros, elephants, and moon bears) to Africa and Asia. “If we don’t want these animals to become extinct, we cannot piously presume that poor countries shoulder that burden all by themselves. That’s like saying we have special privileges,” Trouwborst contends. “What if Tanzania were to say it can only sustain six prides of lions and will cull all other prides, like Norway is currently doing with wolves? That would stir up an international controversy.”

On the plus side, there is now a broad, international rewilding movement that aims to restore ecosystems to the point where they can fend for themselves. The Wildlife comeback in Europe report commissioned by Rewilding Europe was recently issued, Wageningen boasts a new Professor of Rewilding Ecology, and Trouwborst himself is being invited to one rewilding conference after the other. And the United Nations has declared the current decade to be the Decade on Ecosystem Restoration.

Think big

In the Netherlands and in Europe as a whole, roughly four types of action are called for to restore ecosystems: creating substantially more room for nature, dealing with pollution (including nitrogen emissions), removing such physical obstacles as river dams, and returning missing species, Trouwborst explains. “Once that has been done, we can just sit back and relax. Mowing, pruning, weeding, and other forms of labor-intensive management will be surplus to requirements.” It is all feasible, but it is the kind of transition that will take effort. For one thing, we have lost the skills to coexist with large wildlife. Trouwborst: “I fully understand that sheep farmers see wolves as a problem, not as a solution, but the time has come for us to start looking at the bigger picture.”

The climate crisis and especially the biodiversity crisis are the most serious all crises. If we don’t deal with those, their consequences will overtake us on all sides

Are there not simply too many crises on our plate already for us to do that, such as an energy crisis, a labor market crisis, a war on European soil, and an imminent recession? The obvious answer is that good governance means taking the long view, even in times of crisis. Trouwborst shows a cartoon by Graeme MacKay in which the Covid-19 pandemic is a wave dwarfed by the bigger wave of Recession, which itself is being chased by the even bigger Climate Crisis wave, and finally, towering over all, there is the colossal wave of Biodiversity Collapse. “The climate crisis and especially the biodiversity crisis are the most serious of them all,” he says. “If we don’t deal with those, their consequences will overtake us on all sides.”

This also explains his fascination for megafauna and their ecological key role. “My work takes me to Africa quite often and every visit is a special experience. Meeting a buffalo or an elephant is truly exhilarating; it makes me feel tiny as a human. But actually seeing fairly complete ecosystems over there and realizing that Europe also used to have those has changed my outlook. To my mind, the Veluwe region now feels more like a ruin rather than the wildlife Valhalla I once believed it to be. Dreaming of restoration inspires me. Let’s think big.”

Global Law and Governance

The megafauna research is part of the Global Law and Governance research program of Tilburg Law School regarding the role of law in today’s major issues. Arie Trouwborst investigates the local and international roles law plays, as well as the interaction between the two, and he combines his findings with ecological, paleontological, economic, and sociological research outcomes to achieve better practical results.

“In my work, societal relevance has always mattered greatly,” he says. And when that work actually bears fruit, such as not establishing wolf-free zones in the Netherlands (thanks to publications by Trouwborst and his fellow academic Kees Bastmeijer), that pleases him. “Of course, as a researcher I have a duty to conduct my research objectively and impartially, but I do have control over the research question.”

Colofon images: elephant photo by Elvira Martinez Camacho; European bison drawing byJeroen Helmer.

Want to read more?

- Blog by Arie Trouwborst: Megafauna restoration is a legal obligation | Rewilding Europe

- Arie Trouwborst & Jens-Christian Svenning (2022): Megafauna restoration as a legal obligation: international biodiversity law and the rehabilitation of large mammals in Europe In: Review of European, Comparative and International Environmental Law

- Arie Trouwborst (2021): Megafauna rewilding: addressing amnesia and myopia in biodiversity law and policy In: Journal of Environmental Law

Also in Tilburg University Magazine

Date of publication: 31 October 2022