What students can learn from their moral heroes

Every once in a while, special individuals stand up who inspire millions of people. Non-violent Mahatma Gandhi, dauntless Rosa Parks or, more recently, the spirited Greta Thunberg. Who are these moral heroes of our students and what can they teach young people in this day and age? That question is central in the coming academic year in a special Tilburg University project. An interview with political philosopher and project leader Bart Engelen (TSHD) and junior researcher Renée Zonneveld (TSB).

by Doetie Talsma

‘A colleague makes a clearly sexist joke in a meeting. How do you react? And how would your moral example respond?’ These are the type of issues that second and third-year students of Psychology and Business Economics will be addressing in the coming semester.

The idea: by reflecting more consciously on the virtues of your moral hero, you also learn something about your own actions and social responsibility. A lesson that fits the educational profile of Tilburg University, in which, apart from developing knowledge and skills, character development is central.

However, the three-year project entitled ‘The role of moral examplar interventions in academic character building’, goes beyond just education. Students can also participate in a study that is part of a large, international research project on leadership and character, financed by the John Templeton Foundation. An interview with political philosopher and project leader Bart Engelen (TSHD) and junior researcher Renée Zonneveld (TSB).

The project has an impressive title. What do you refer to with moral examplars and interventions?

Bart Engelen:

“A moral examplar is someone who you look up to from a moral point of view. You can look up to athletes because of their athletic abilities, but you can also admire people who are very good in the ethical domain. There are a number of famous moral heroes, for instance Nelson Mandela, Rosa Parks, or nowadays Greta Thunberg. But you can also admire a parent, sister, or friend for the way they live their lives or tackle difficult situations.

“We also refer to them as moral heroes. Not super heroes, no superhuman types, but meritorious people who display admirable behavior, for example, because they are very brave, steadfast, or compassionate. They don't have to be saints or perfect people.”

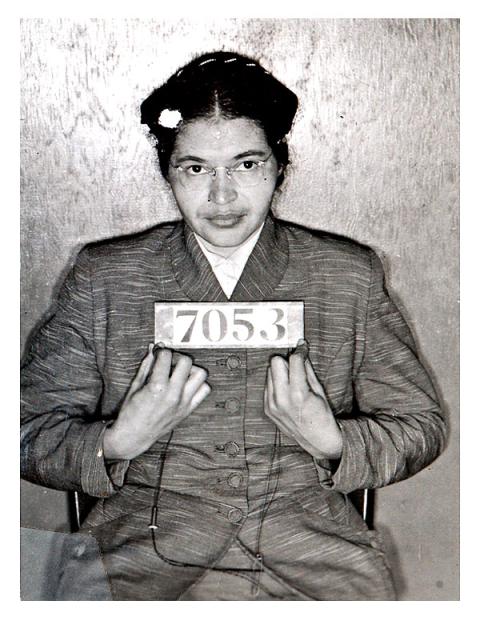

Alabama 1955: Rosa Parks was arrested because she refused to give up her seat in public transport to a white passenger. Beeld Flickr / GPA Photo Archive

What role do these heroes play in the lectures?

Renée Zonneveld:

“During classes, students choose their own moral examplar. Subsequently, we will let them think further about these people. Why did I choose this person? What are the norms and values that I admire so much? What of his or her behavior can I take on board in my own life?

“Students will also discuss topics together: what agreements can be found and in what ways do we differ in our choice of moral heroes? By exchanging thoughts about this, you become more aware of how you want to live your life.”

Engelen:

“And that is also the reason why we ask students to choose an examplar themselves rather than telling them: ‘Here is Nelson Mandela, apply him to your own life.’ It insufficiently invites students to think for themselves on the ethical nature of their own actions, norms, and values. If you think more consciously about who you admire, that person can, in one way or another, be meaningful to you, for example, if you face a dilemma.”

Zonneveld:

“Moreover, no one is 100 % good. So it is also important to explore the things you might not want to take over from your hero.”

And then this concept of character, the third pillar of the Tilburg Educational Profile (TEP). What exactly does that mean?

Engelen:

“A character is an integrated whole of stable personality traits. The tendency to consistently act in a certain way. In ethics, we call positive character traits virtues, for instance, honesty; that is part of your character. You are an honest person, so when you act or talk to people, you are inclined to be truthful.”

Zonneveld:

“It is mainly about a person’s positive characteristics, for instance, courage, modesty, honesty, or gratitude. Social character traits that we appreciate in people.”

But is character always something positive? You can also have negative character traits, can’t you?

Engelen: “

Certainly. The literature describes the vices, as opposed to the virtues. You also have people with a thoroughly bad character. But if we want to help a character grow, we want it to develop into the right direction. The vices can also be stimulated, but that is obviously not our objective.”

Why should character development be a university’s business?

Engelen:

“We would make a very poor show if we merely provided students with knowledge and skills in preparation for the job market. What you are saying is: ‘Here is a lot of knowledge, we train you in a few skills, and that’s it. Good luck to you.’ That would reflect a very instrumental view of what a university should be trying to achieve.

We would make a very poor show if we merely provided students with knowledge and skills

“We, and I think I speak for the university as a whole, want students to become independent and critical thinkers. That they have the courage to be responsible for their own thought processes and that they bear the consequences for their own actions and dare to stand up for them. You could call that character: certain attitudes that you try to stimulate in students.”

Does the diploma state something about a student’s character?

Engelen:

“The university has introduced character development into the Educational Profile a number of years ago. It is now beginning to emerge through its implementation into courses. In these courses, we test to what extent students acquire certain skills and attitudes, but of course we do not grade students’ ‘intellectual independence’. Whether and how we are going to measure character development, and how this will be reflected on a diploma, those are questions to be answered in the coming years.”

In addition to teaching about this subject, you are also conducting research into character development among students.

Zonneveld:

“That is right. Psychology and Business Economics students taking the courses in which we work on moral examplars can also sign up for our research project. They take a number of supplementary classes, complete questionnaires, and do a writing assignment. In return, they receive experimental-subject hours or a financial consideration.”

Engelen:

“For the Business Economics students, for example, the research project is integrated into the Business Ethics course. ‘Moral conduct’ within a company is the central theme. We can measure the effect of the classes on this theme and the writing assignment on students participating in our study.”

What effects do you expect to see?

Engelen:

“We want to fill a number of gaps in the existing literature on the subject. There is consensus on the fact that thinking about your moral examplar also makes you think about who you are as a person and what you think is important in life. But not a lot is known about how exactly this works. How it leads to different behavior. And to character virtues.

“Our project mainly zooms in on the role of emotions, for instance, admiration. In the light of the Black Lives Matter protest movement, you can choose Rosa Parks as your model and look up to her, but what happens when you look up to someone? Do you become energized so can work up the courage to become active yourself? Or is there a different dominating emotional reaction?

“Parks was rightly angry about the injustice of her time. Do you share her indignation? By mapping the emotional make-up of our experimental subjects, we hope to see what things change over time.”

Finally, who are your own moral heroes?

Zonneveld:

“For me, it is not a very well-known person, but a YouTube group: The Mischief Managers. A group of Harry Potter fans who have created a space on YouTube that is very inclusive of transgender and other people in the LGBTQ community. To me, they are moral examplars because they are so open themselves about their own norms and values and can thus help and include other people.”

Engelen:

“For me, it is Father Damien, a Belgian priest, who was also voted the greatest Belgian of all time, a moral hero. He went on a mission to the island of Molokai to help for leprosy victims. Ultimately, he also contracted the disease and died in Molokai. He is an iconic example of someone who very consistently lived according to his values at the expense of his own interests.

“A more everyday examplar is my mother. For years, she cared for my ailing father, who has since died. I admire her because she always found the strength to be positive, even in very difficult times.”

Do you want to participate in the study? Sign up for the pilot study!

Students who are interested in this research project can register for the pilot study. The pilot is a short version of the project, whereby you complete questionnaires but do not attend classes or submit writing assignments.

- For Dutch students:

De Rol van Voorbeeld Interventies voor Academische Karaktergroei - For international students:

The Role of Emotions in Exemplar Interventions for Academic Character Building

This article was previously published in Univers.